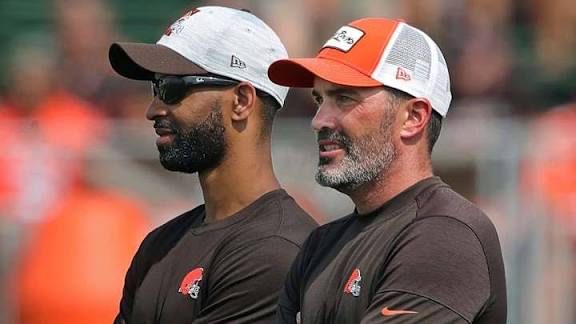

Tiger Woods and Rory McIlroy look on from the 11th tee during a practice round prior to the 2023 Masters Tournament at Augusta National Golf Club on April 03, 2023 in Augusta, Georgia. (Photo by Christian Petersen/Getty Images).

Committees often have about as much utility as ashtrays on motorcycles, and in golf usually serve only as a mechanism to butcher great courses and honor the milquetoast. On occasion, however, they can be impactful. The three-man panel that negotiated the PGA Tour’s Framework Agreement with the Saudis last summer certainly made an impression, not least because other Policy Board members didn’t know of its existence nor much care for its output.

The backlash to that secretive process sparked a time-consuming and overdue governance review that is essential as the Tour shapeshifts from an indolent non-profit with complacent members into a modern league with shareholders and investors. A handful of oversight committees have now been established at PGA Tour Enterprises, the for-profit entity that runs the business. Most are standard operating procedurals, but one panel in particular suggests the Tour is about to move beyond childish bickering and begin letting grown-ups shape its future.

The Transaction Subcommittee’s anodyne name belies its importance. It will handle talks with the Public Investment Fund of Saudi Arabia on a potential deal and make a recommendation to the full Policy Board — one the politburo is unlikely to reject from its hand-picked negotiators. Committee members include Enterprises chairman Joe Gorder, commissioner Jay Monahan and John Henry, the principal of Strategic Sports Group, which just invested a billion-five into the product. There are also four players: Joe Ogilvie (retired, and now a humble money manager), Tiger Woods, Adam Scott and Rory McIlroy. In short, a lot of people unaccustomed to making business calls by committee.

No one is on the panel to present moral arguments about being in business with a despot. Those who harbor any such reservations will check them at the door and treat negotiations as a matter of commerce, not conscience. But it is at least a committee of adults, something sorely needed in this sorry mess.

The PGA Tour has been consumed with dual crises, one internal, one ex-. The latter is obvious — the LIV threat, caused by the depth of Saudi pockets and the shallowness of character among the Tour’s own membership. The internal dispute mostly remained behind boardroom doors until spilling into the open this week when a faction of player-directors (Woods, Patrick Cantlay and Jordan Spieth) blocked an effort to reappoint McIlroy to the Policy Board he left six months ago.

The rebuff wasn’t unjustified. There must be a legitimate and transparent process governing board appointments and having Webb Simpson nominate McIlroy as his successor ain’t either. Still, there was no hand-wringing when Woods was added to the board in the middle of the night, the only member without (still) an expiration date for his term. The Pope of Ponte Vedra serves at his own discretion, it seems. But the stiff-arming of McIlroy exposed how personal grievances have masqueraded as governance concerns.

There are ample misgivings about how the Tour is run and most are genuinely held and valid. But some guys just remain angry at being blindsided by the Framework Agreement, while others are pissed because they left LIV’s millions on the table and know their moment has passed. They want the heads of those who architected the June 6 deal — Monahan, Ed Herlihy and Jimmy Dunne — and the thirst for retribution has paralyzed the organization at a perilous time.

That faction sees McIlroy as too close to their nemeses, but in balking at his return to the board they might have overplayed their hand. A public perception now exists that the Cantlay camp wields power, which means that credit for progress — or, more likely, blame for a lack thereof — is destined for the same desks.

Thus McIlroy now finds himself used by both sides. Having long been a proxy for executives in fighting the public battle against LIV, he is now seconded to the Transactions Committee as a convenient means of providing cover for the players who didn’t want him to have a board vote, but who fear even more scrutiny for having rejected him. The Tour is fortunate that he’s sufficiently toughened (or soft) to endure its maladroit bungling in his effort to contribute to a solution. McIlroy’s relationships with stakeholders on both sides will be useful to the committee, but not enough to single-handedly forge a settlement in golf’s civil war. Even a good-faith effort might still mean the Tour moves forward without a toxic association with the PIF.

Whatever the outcome, the spectacle of backroom squabbling has focused a harsh light on the role of players in management. The to-ings and fro-ings of recent years prove that most players will make decisions based upon personal priorities, not the broader good of the sport or a tour. That tendency is incompatible with the executive functions they now feel entitled to exercise.

If nothing else, perhaps this committee will hasten a day when all of them can get back to adding value where they do it best — inside the ropes — and leave the actual business to those qualified for the challenges.